COUNTRY CODE

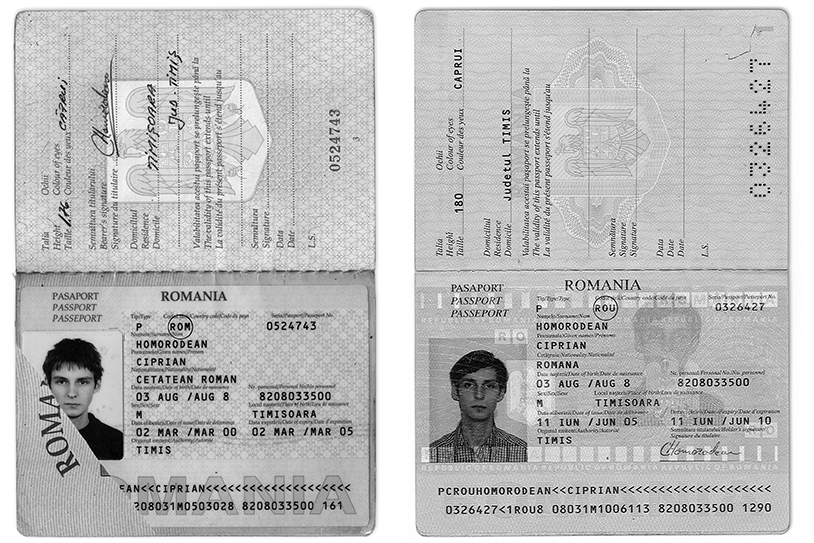

Country Code, c-print, 2007.

I noticed the change on Romanian passports by chance: the old country code “ROM” had been replaced with “ROU”. This change wasn’t made randomly, of course, but for fear that ROM could be interpreted as a reference to the Rrom (gipsy) population. Romanian authorities had obviously noticed that the country’s image would suffer if there was confusion between “Rroma” and “Român” (Romanian). This brought to mind a comment I had heard four years ago, when I was travelling to an art symposium in Hungary. The Romanian sculptor Dumitru Painea had been indignant at having ROM written on his passport; he would have preferred DAC, he said, because he considered himself a Dacian.

It will help to follow some of the threads that have contributed to weave the Romanian identity and their perception of the Rrom in order to grasp this artist’s comment, and to perhaps better understand the fears that instigated this small yet significant country code change in Romania.

In history class under Communism, history lessons started with the Daco-Romans, presented to us as the sole and mighty ancestors of the Romanian people. We then went on to study the history of the various occupations and oppressions our people had to endure before finally arriving to the Communist period. Our very people, we were taught, perpetuated the greatness of our origins; we were as great as our Dacian fathers. Indeed, Romania is quite a young country –gaining official recognition only in 1878-, but the prolonged nationalist propaganda, practiced intensively during the years of Ceausescu’s reign, left profound marks in Romanian consciousness. Furthermore, as art theoretician Marius Babias has pointed out, the process of this “fake” identity construction was longtime in the making:

“Having been politically and culturally ostracized after the Second World War, Romanian intellectuals, artists and writers tended towards a national discourse which contributed to the construction of a Daco-Roman continuity beginning in antiquity, when Romania was born as a Latin nation, having its ethno-genesis in the mixture between the native Dacians and the Roman colonists. This continuity was considered to have survived right up to the advent of Communism, where it somehow culminated with Ceaucescu, the apparently legitimate standard bearer of Romanian national history. Ceaucescu’s personality cult started developing in the 70’s, projecting the self-proclaimed leader as an analogue of the mythic figure of the Dacian king, Decebal.”

Another idea presented to us in Romanian history class was the kindness of our people. Two recurring mottos summed up our nature: “Romanians led only defensive wars” and “Romanians never did ill to anyone”. This did not apply to the Rrom, however. As it turns out, the first Rrom, attested in Moldavia (1428) and in Muntenia (1385), are referred to in the texts documenting their history as property of several monasteries. In other words, slaves. Actually, when the Rrom arrived, slavery was already commonly practiced in the Romanian principalities, organized into different categories: princely slaves (belonging to the prince or the state), boyar slaves (slaves of the nobility) and monastery slaves. Among all of these, the Rrom had a place of choice. And although some official documents dating from the17th Century referred to them as rob (slave), the term Tigan (Romanian for “gypsy”) was, since the 15th Century, synonymous of slave. This explains in part why nowadays it is preferable to use “Rrom” rather than “Tigan”.

By 1818, according to the penal code of Muntenia, it was commonly agreed that “all gypsies are born slaves”, and “gypsies without owners are the property of the state”. Throughout the 19th Century, the changes in the economy would contribute to further penalize this population, as slavery became yet another venue for the market economy and slaves just another merchandise, sold and bought in large numbers.

The installation of authoritarian regimes in Romania and their adoption of racist legislation policies would bring even more dramatic changes for the Rrom. An ethnical purification program, launched in 1942 by the government of Ion Antonescu, led 25,000 Rrom (approximately 12% of the total Rrom population in the country) to be deported from Romania to the actual Transnistria. Exposed to hunger, cold, and disease, about 11,000 of the deported would perish under extremely rough living conditions. By 1948, the Communist regime had switched to a policy of forced “sedentarization” of nomad gypsies: the wandering people were coerced to settle down, having their horses and wagons confiscated if necessary. Racial issues had apparently given way to a quest for public order and “moral sanitation”; it was time to impose the “cult of work”. This forced assimilation of the Rrom into the communist regime relied on the concept of social homogenization, where the model of the new “Socialist man” was to flourish. Perceived as foreign elements that had to be somehow integrated, all arguments would be used to justify their assimilation. Yet, the ethnic heritage of the Rrom made them a particularly hated population, viewed as having an inferior social status, belonging to a poor and underdeveloped culture, and more generally representing a threat to civilization. What’s more, most of their traditional activities were considered at the limit of legality, catalogued as “social parasitism”, “anarchism” or other types of “deviant behavior” which could be punishable with imprisonment and forced labor.

The Rrom were to confront yet another predicament under Ceausescu, who, in his efforts to pursue the “assimilation” of the Rrom population, pushed them into a situation of even more rejection. Forced to abandon their traditional way of life, the Rrom were settled in government housing and put to work in the agricultural and heavy industry sectors. Yet, far from integrating, their presence among the Romanian population was unwelcomed; they were generally disliked and perceived as dangerous, unwanted intruders. Also, in a most unusual approach, during this period it became a common practice to simply ignore the Rrom. The official discourse thus symbolically banished them: in the 1980’s, gypsies no longer existed in Romania. As some authors have suggested, the policies carried out during the Ceausescu era might have been part of a larger plan to bring forth the alleged superior Dacian race, a scenario where the Rrom, encouraged to reproduce under strict government control, would have formed a “robot work force”, sparing the true and pure Romanians from menial work. Notwithstanding the veracity of this macabre plan, the attitudes and policies of Romanian authorities so far described most certainly contributed to foster antagonistic feelings towards the Rrom population.

In his lucid analysis of the emergence of a post-Communist European identity, Marius Babias laments the absence of a critical processing of history, which reduces identity construction mechanisms to rely only on the “presentation of a continuity of the national history, myths, traditions, and cultural self-appreciations”. Thus the “process of reorganizing both post-Communist society and the self as European” is set on fallacious grounds. To make matters worse, he observes, the new elites, who play an important role in constructing the national identity, are simply rephrasing the old Communist national discourse using the terms of the now dominant liberalism. Evolving on such shaky grounds, it seems quite unlikely that Romanians could ever admit the Rrom among them. In fact, although after the collapse of the Ceausescu regime some efforts were made to grant more recognition to the Rrom minority within Romanian society, they often met with rejection or were simply not followed through.

Caught in a vicious circle of lack of respect, lack of interest, and lack of understanding on the part of the Romanians, the Rrom appear to be condemned to a social existence that can only lead to more discrimination. Too many preconceived ideas persist, sustaining the negative mental images that have been constructed over time. Nothing is done to offer the Rrom the conditions for a real access to full Romanian citizenship.

Viewed as a social sore and considered by many to be genetically inclined to crime, the Rrom are the national scapegoat, “automatically blamed for everything”. Since the 1990’s, many have sought refuge abroad, for, as a Rrom intellectual explained: “the risks involved in being a Gypsy in Romania in 1990 persuade all those offered the opportunity to take refuge abroad; perhaps it is no better there, but at least you can nourish the hope that it is up to you alone too maintain your dignity”. Unfortunately, this has only increased the anti-Rrom sentiment of Romanians, who blame the gypsy living in other countries for giving a bad image of Romania; it has also given rise to new discriminative attitudes in other parts of the world. For complex reasons that are difficult to isolate, and also very hard to accept, Romania’s bad reputation tends to hold in the West. Both at home and abroad, it’s easy to blame the ill-reputed Rrom for this, taking some isolated cases as confirmation of their evil influence and their criminal nature. The media continues to exploit this vein, using tendentious headlines, and reporting on outrageous events, such as the incident of the gypsies who ate the swans of Schönbrunn Palace, in Vienna. Anecdotes such as this represent the lighter side of the general discourse surrounding the Rrom, a discourse that has toughened over the past years. The confusion appears to be growing as international politicians publicly condemn the Rrom population as a whole and introduce discriminatory legislative actions against them.

All this goes to prove how dangerous it is to ignore history; it will invariably result in deformations leading, in this case, to nationalist feelings impregnated with racism and to unjust amalgamations that tarnish even more the victims of discriminative perceptions. In today’s globalized context, we owe it to the world to embrace history within its larger frame, widening our horizons to include the ensemble of society. After all, there is not such a big distance between an “M” and a “U”.

It will help to follow some of the threads that have contributed to weave the Romanian identity and their perception of the Rrom in order to grasp this artist’s comment, and to perhaps better understand the fears that instigated this small yet significant country code change in Romania.

In history class under Communism, history lessons started with the Daco-Romans, presented to us as the sole and mighty ancestors of the Romanian people. We then went on to study the history of the various occupations and oppressions our people had to endure before finally arriving to the Communist period. Our very people, we were taught, perpetuated the greatness of our origins; we were as great as our Dacian fathers. Indeed, Romania is quite a young country –gaining official recognition only in 1878-, but the prolonged nationalist propaganda, practiced intensively during the years of Ceausescu’s reign, left profound marks in Romanian consciousness. Furthermore, as art theoretician Marius Babias has pointed out, the process of this “fake” identity construction was longtime in the making:

“Having been politically and culturally ostracized after the Second World War, Romanian intellectuals, artists and writers tended towards a national discourse which contributed to the construction of a Daco-Roman continuity beginning in antiquity, when Romania was born as a Latin nation, having its ethno-genesis in the mixture between the native Dacians and the Roman colonists. This continuity was considered to have survived right up to the advent of Communism, where it somehow culminated with Ceaucescu, the apparently legitimate standard bearer of Romanian national history. Ceaucescu’s personality cult started developing in the 70’s, projecting the self-proclaimed leader as an analogue of the mythic figure of the Dacian king, Decebal.”

Another idea presented to us in Romanian history class was the kindness of our people. Two recurring mottos summed up our nature: “Romanians led only defensive wars” and “Romanians never did ill to anyone”. This did not apply to the Rrom, however. As it turns out, the first Rrom, attested in Moldavia (1428) and in Muntenia (1385), are referred to in the texts documenting their history as property of several monasteries. In other words, slaves. Actually, when the Rrom arrived, slavery was already commonly practiced in the Romanian principalities, organized into different categories: princely slaves (belonging to the prince or the state), boyar slaves (slaves of the nobility) and monastery slaves. Among all of these, the Rrom had a place of choice. And although some official documents dating from the17th Century referred to them as rob (slave), the term Tigan (Romanian for “gypsy”) was, since the 15th Century, synonymous of slave. This explains in part why nowadays it is preferable to use “Rrom” rather than “Tigan”.

By 1818, according to the penal code of Muntenia, it was commonly agreed that “all gypsies are born slaves”, and “gypsies without owners are the property of the state”. Throughout the 19th Century, the changes in the economy would contribute to further penalize this population, as slavery became yet another venue for the market economy and slaves just another merchandise, sold and bought in large numbers.

The installation of authoritarian regimes in Romania and their adoption of racist legislation policies would bring even more dramatic changes for the Rrom. An ethnical purification program, launched in 1942 by the government of Ion Antonescu, led 25,000 Rrom (approximately 12% of the total Rrom population in the country) to be deported from Romania to the actual Transnistria. Exposed to hunger, cold, and disease, about 11,000 of the deported would perish under extremely rough living conditions. By 1948, the Communist regime had switched to a policy of forced “sedentarization” of nomad gypsies: the wandering people were coerced to settle down, having their horses and wagons confiscated if necessary. Racial issues had apparently given way to a quest for public order and “moral sanitation”; it was time to impose the “cult of work”. This forced assimilation of the Rrom into the communist regime relied on the concept of social homogenization, where the model of the new “Socialist man” was to flourish. Perceived as foreign elements that had to be somehow integrated, all arguments would be used to justify their assimilation. Yet, the ethnic heritage of the Rrom made them a particularly hated population, viewed as having an inferior social status, belonging to a poor and underdeveloped culture, and more generally representing a threat to civilization. What’s more, most of their traditional activities were considered at the limit of legality, catalogued as “social parasitism”, “anarchism” or other types of “deviant behavior” which could be punishable with imprisonment and forced labor.

The Rrom were to confront yet another predicament under Ceausescu, who, in his efforts to pursue the “assimilation” of the Rrom population, pushed them into a situation of even more rejection. Forced to abandon their traditional way of life, the Rrom were settled in government housing and put to work in the agricultural and heavy industry sectors. Yet, far from integrating, their presence among the Romanian population was unwelcomed; they were generally disliked and perceived as dangerous, unwanted intruders. Also, in a most unusual approach, during this period it became a common practice to simply ignore the Rrom. The official discourse thus symbolically banished them: in the 1980’s, gypsies no longer existed in Romania. As some authors have suggested, the policies carried out during the Ceausescu era might have been part of a larger plan to bring forth the alleged superior Dacian race, a scenario where the Rrom, encouraged to reproduce under strict government control, would have formed a “robot work force”, sparing the true and pure Romanians from menial work. Notwithstanding the veracity of this macabre plan, the attitudes and policies of Romanian authorities so far described most certainly contributed to foster antagonistic feelings towards the Rrom population.

In his lucid analysis of the emergence of a post-Communist European identity, Marius Babias laments the absence of a critical processing of history, which reduces identity construction mechanisms to rely only on the “presentation of a continuity of the national history, myths, traditions, and cultural self-appreciations”. Thus the “process of reorganizing both post-Communist society and the self as European” is set on fallacious grounds. To make matters worse, he observes, the new elites, who play an important role in constructing the national identity, are simply rephrasing the old Communist national discourse using the terms of the now dominant liberalism. Evolving on such shaky grounds, it seems quite unlikely that Romanians could ever admit the Rrom among them. In fact, although after the collapse of the Ceausescu regime some efforts were made to grant more recognition to the Rrom minority within Romanian society, they often met with rejection or were simply not followed through.

Caught in a vicious circle of lack of respect, lack of interest, and lack of understanding on the part of the Romanians, the Rrom appear to be condemned to a social existence that can only lead to more discrimination. Too many preconceived ideas persist, sustaining the negative mental images that have been constructed over time. Nothing is done to offer the Rrom the conditions for a real access to full Romanian citizenship.

Viewed as a social sore and considered by many to be genetically inclined to crime, the Rrom are the national scapegoat, “automatically blamed for everything”. Since the 1990’s, many have sought refuge abroad, for, as a Rrom intellectual explained: “the risks involved in being a Gypsy in Romania in 1990 persuade all those offered the opportunity to take refuge abroad; perhaps it is no better there, but at least you can nourish the hope that it is up to you alone too maintain your dignity”. Unfortunately, this has only increased the anti-Rrom sentiment of Romanians, who blame the gypsy living in other countries for giving a bad image of Romania; it has also given rise to new discriminative attitudes in other parts of the world. For complex reasons that are difficult to isolate, and also very hard to accept, Romania’s bad reputation tends to hold in the West. Both at home and abroad, it’s easy to blame the ill-reputed Rrom for this, taking some isolated cases as confirmation of their evil influence and their criminal nature. The media continues to exploit this vein, using tendentious headlines, and reporting on outrageous events, such as the incident of the gypsies who ate the swans of Schönbrunn Palace, in Vienna. Anecdotes such as this represent the lighter side of the general discourse surrounding the Rrom, a discourse that has toughened over the past years. The confusion appears to be growing as international politicians publicly condemn the Rrom population as a whole and introduce discriminatory legislative actions against them.

All this goes to prove how dangerous it is to ignore history; it will invariably result in deformations leading, in this case, to nationalist feelings impregnated with racism and to unjust amalgamations that tarnish even more the victims of discriminative perceptions. In today’s globalized context, we owe it to the world to embrace history within its larger frame, widening our horizons to include the ensemble of society. After all, there is not such a big distance between an “M” and a “U”.

Reference texts:

Viorel Achim, Tiganii in istoria Romaniei / Gypsies in Romania’s History, Editura Enciclopedic/ The Encyclopedic Publishing House, Bucuresti / Bucharest, 1998

Marius Babias, Eurosinele si europeismul / The Euro-self and the Europeanism, IDEA, arta + societate / art + society, Nr. / No. 24/2006

David M. Crowe, A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 1995

Andre Stanescu, “Sclavia rromilor” / “Slavery of the Rrom”, 2004: http://www.rroma.eu